Conflict, peace, conflict

One of the most influential works I’ve ever read is Eric Hobsbawm’s “long nineteenth century” trilogy on the development of society from the French Revolution through the industrial revolution. I read the final book, Age of Empire, in the days leading up to the 2016 election, while on a trip in Malaysia. Hobsbawm wrote with much evidence for many of his arguments but a relatively unsupported comment he made about the attitudes of the European elite in the leadup to WW1 have stood out to me more than anything else in his long analysis. A very rough summary would be that WW1 came about because young Europeans had not faced any significant external conflict in their lifetimes, and they were bored! Both I, and Hobsbawm, reduced multiple contributing factors to a general sense of angst, with no other good outlet to channel it. Could such a huge global era with a legacy lasting a hundred years really come about because of a vague ennui? The front page of the Malaysian newspaper the day I finished that book showed a big image of Donald Trump.

A lot has happened since 2016 that would support the idea that we as a global society are caught in a tension between the individual frustrations of a given populace, and world order that generally prefers peace (largely for economic reasons). Plenty has happened in the first 100 days of the second Trump administration which make me feel we are truly teetering on the brink.

The next end of history

If Francis Fukuyama coined the phrase “the end of history” at the end of the cold war, Hobsbawm had basically already found and called a prior end of history in his work on the long nineteenth century (though just a few years before Fukuyama). The insight at the core of Fukuyama’s declaration was that with the USSR’s collapse, the world was essentially unipolar (the USA), liberal democratic, and capitalist, and as such unlikely to continue in the manner of constant global conflicts as it had since the outbreak of WW1 (a range of time Hobsbawm called the “short 20th century”). Though Fukuyama’s reputation was then cast in stone for predicting some long-lasting peace, another of his comments in the same work has seemed at least to me to become more insightful – “If men cannot fight for a just cause… then they will fight against the just cause…for the sake of struggle”

It’s been somewhat well-theorized that boom and bust cycles come around in human society every 50 years, though perhaps that’s a conclusion dictated more by the timeframe studied, a 150 year period with a large amount of tumult in the middle. The Belle Epoque that preceded the outbreak of WW1, and the 1990s and early 2000s in the US, invite comparison for the deepening of global interdependence and the rapid technological accelerations that were hallmarks of both eras, with clear pockets of outsized beneficiaries living lives drastically different from the disfavored. We like to point to concrete events like the assassination of Franz Ferdinand or Hitler invading Poland as the triggers for war, but Hobsbawm and Fukuyama both suggest the real reason is an underlying cultural whine that reaches a fever pitch. You could argue that the era from 1990 until roughly somewhere between Brexit in 2016 and Trump 2 in 2024 represented a “long 19th century”-esque period of calm; 30 years where the US was in a hegemonic global position and largely used that power to enforce a regime of democratic capitalism that, aside from small conflicts in the Middle East, kept global powers aligned and out of conflict. There are signs though that something about that era is fading and we may be coming into a “short 21st century”.

Are we entering a new “short” cycle?

Politics in the US since 2016 has seen a notable decline in politeness. “Polarization” is the more common term, but there’s something existentially more terrifying about the situation in the developed world in the last 10 years that goes beyond mere gravitation in preferences towards a pole on a policy issue. Trust in government surveys show we are today at an all-time low. There is a desperation across the populace. Two wars that have polarized populations across the world have sprung up in regions that otherwise had seen long periods of relative peace. And above all, people are mean! Why?

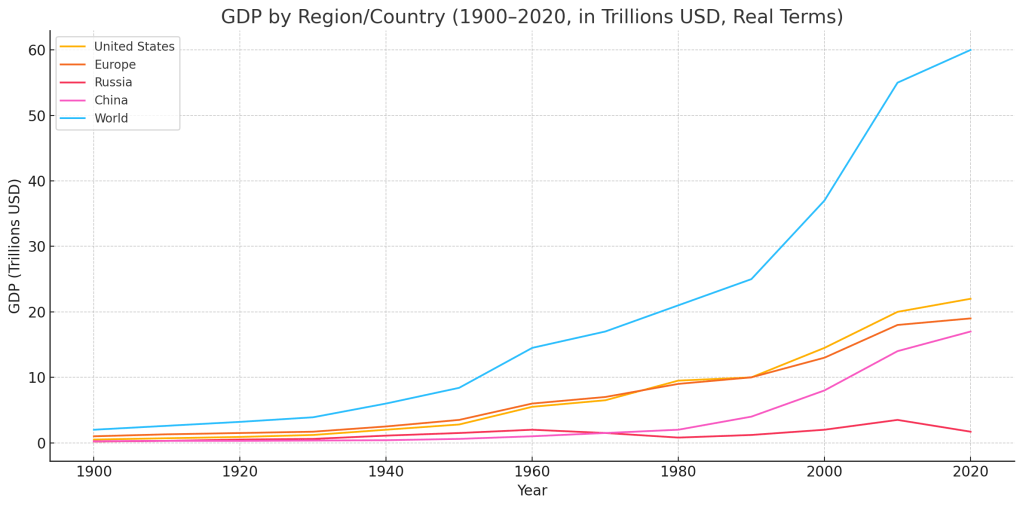

If we ARE entering a new short cycle, it is hard to conclude that it’s because of a decline in objective advantage for the US versus other countries. The US has been the dominant force in global GDP since the end of World War II. The only lag has been in the distance of the gap between the US and multiple other countries, specifically China, and the fear of looking in the rear view mirror and losing the lead (even though we will unquestionably have it) has motivated us to make decisions based on an assumption that we must maintain our hegemony at all costs. This Thucydides Trap is one way to understand the current political dynamic in America.

Regardless, the decision seems to have been made by the current administration that we must act now and drastically to do something about the above chart, and the action is to apply massive tariffs of some severity on every other country in the world. There are tons of reasonable debates going on about tariff policy as an economic tool, whether the policy is rolled-out well, whether it is a good fit for the problems the Republican party has suggested they will solve. It’s been a great month for the podcast industry and the financial newsletter industry. These questions all generally frame themselves as questions about the country GDP chart above, and the trajectories of the lines, and how to change them. These are important questions! But I’m not an economist, and I ultimately believe Trump won’t end up doing much of anything because the backlash is too severe. I’m also not certain that tariffs, or any of Trump’s other policies, are actually ABOUT GDP, or manufacturing, or any of their claimed goals, but rather exist solely as a possible response to the angst that Trumpism has captured.

The question I’m interested in is why there is such an angst to be captured. Specific economic or governmental policy aside, the objective data on the state of the United States has diverged from the sentiment of its people. Why, and what would need to happen to reconnect them?

Indicators of a Fracture

Social media isolation // over-exposure

The New York Times had a great article headline about crypto millionaires in 2018 – “Everybody is getting hilarious rich and you’re not”. The article itself was all about the runup in crypto prices that had launched many talentless idiots into a stratosphere of wealth usually reserved for people who had plied some valuable trade into the world, and the ways these fools were both wasting money in fantastic fashion while also making everybody else feel even more foolish for not having shared in their luck.

It’s a great headline, and an article that’s stuck with me, because it so well traces a dynamic that pervades our last ~10 years of internet culture. It’s not really that there are that many more people in the world richer than you, it’s that you SEE representations of of that wealth on social media in a pervasive manner. The perception that any given individual has of their own relative wealth is constantly challenged by these depictions of other people’s success. I’m not certain what life was like it 1980, but I doubt an average American was as inundated with images and videos of other people’s success (real or fake) like we are in the social media era today where videos of high-rise apartment tours in Miami garner millions of views. We may indeed live in an era of opulence, perhaps something we will only recognize fully in retrospect, but in past eras it was not so easy for the unlucky to see the lives of the lucky as social media forces us to witness today. TikTok, Instragram, and “X.com” have made it more likely than ever that a given person will somehow feel both far poorer than they are and relatively isolated in that reality – a sort of retrospective FOMO, because you already missed out.

The main subject of the NYTimes article is such a great encapsulation of this energy, and crypto if nothing else may be remembered as a wonderful barometer of the desperation to be wealthy that so many have. The article mentions a housekeeper who put all their money in crypto while acknowledging that they may “lose it all”. A technology that financially monetized FOMO is truly an invention of the 2010s and early 2020s, and perhaps inadvertently the price of bitcoin has become a direct tracker for people’s lack of faith in a more traditional system to make them hilariously rich. It’s easier then to understand the average person’s affinity for Donald Trump’s presidential pitch, which always resonates when he’s the challenger; MAGA is a “get rich quick” pitch, cast in the light of presidential legitimacy. And since get rich quick schemes don’t actually work, Trump seems to quickly lose his appeal once empowered to enact whatever policy is meant to rid us of the scapegoats that have not in actuality caused our perceived decline, or whatever economic or social policy he has promised with make us wealthy again does not.

Social media’s impact on our society is extremely under-studied, because a large percentage of the US population is in complete denial about technology’s ability to influence us so directly but subtly. But there is plenty of evidence that the major powers of the world view social media as a weapon in international competition – be it the significant Russian influence campaigns in the 2016 and subsequent US elections, or Chinese complete control of the narratives their own citizens are exposed to (and increasingly that a portion of the US is exposed to via TikTok), it’s reasonable to conclude that only the US has missed the boat in tracking and controlling the influence new media has on it’s own country.

Gamergate / and the Manosphere

My dad, a ~65-year old boomer who lives in the Midwest but is socially liberal, recently caught up on “The Last of Us” on HBO. After it’s conclusion he asked me if there was something about my generation and “characters in shows being gay”. My initial distaste for his question included, this short interaction encompasses something quite telling about the zeitgeist of our time.

As I wrote and thought about the impact of social media, and the decline in economic well-being, the rise of commonplace gender discourse particularly around “Men” and male aversion to “wokeness” felt as or more significant as any other single trend in tracing our path to the current moment. My dad inadvertently wandered into multiple of these topics at once in his simple “why is Ellie gay” question. My generation grew up with one somewhat significant civil liberty cause, the right to gay marriage. Prior generations fought for civil rights for minorities, or women, and our cause had been gay rights. We tidily wrapped that one up and then liberals in our country started to debate what to do next. Unfortunately the answer was “face complete societal resistance to every other issue you might choose”, be it guns, trans rights, or abortion expansion. Men, mostly white, but not just “conservative”, became the resistance to all of those issues.

Gamergate was a “movement” that arose in 2014 in the video game world, and in retrospect was one of the early signs that there was a simmering backlash against liberal social causes largely from white men. This was a sensible place to find this movement, if it was brewing generally; gaming, especially at the time, is a predominantly younger and more white, more male demographic. The inciting incident for the movement ended up being false, an early harbinger of the challenges we have today with ‘fake news’ and its ability to spread before it can be debunked. But the sentiment of the gamergate movement, that minority voices were being amplified to an extent that made the majority feel itself marginalized, is one that lines up quite well with cultural underpinnings of Trumpism and it’s naked majority culture self-interest.

As liberalism failed to find a new cause that appealed to a broad coalition, the essential narrative of gamergate pervaded into other parts of culture and took purchase as the “counter” to many stillborn socially liberal efforts. Many left-leaning commenters over the years pointed out that causes like trans rights, and purity tests around their support, would not be likely to yield a large coalition but their largely political observations understated the grave shift that was occurring. The covid pandemic proved to be quite an accelerator, particularly during the Black Lives Matter movement which likely did more to inspire Trumpism in white communities than it did to inspire anti-Trumpism in minority communities. Covid also pushed more people into an online bubble, where largely conservative voices had found success after themselves being pushed out of the mainstream. Ironically as the media landscapes flipped, the online bubbles became the mainstream, and now this land historically dominated by crackpots like Alex Jones became as influential in shaping public narratives around facts as previously mainstream journalism. The last election was likely more shaped by the words of Joe Rogan, Andrew Huberman, and Lex Fridman, than it was by Wolf Blitzer or Jake Taper, and at least some of Trump’s success was credited to a superior media strategy of targeting mass audience podcasts and their predominantly male listener bases, more recently termed “the manosphere”. The fact that a major Trump supporter and future unofficial cabinet member Elon Musk owned one of the largest social media platforms seems now under-considered as a factor in his win.

The short cycle of WMYONT (White Men Yelling On Twitter)?

In search for a single cause to explain the decline in comfort with the status quo in America over the last 10 years, I find many compelling signals of fragmentation. But as in prior antecedents to ‘calm’ global eras, our current moment feels more molded by an ennui that social media and a lack of an otherwise unifying cause have amplified. A gap, an abscess of meaning, that has been filled with amplified mild discomfort. But over time, the amplified discomfort became the problem – “White men yelling on twitter” is itself the problem, the cause of the problem, and ironically the solution to the problem as those loud caucasian males ended up in both the presidency and vice presidency. There’s no single thing they are yelling about, but rather a near endless sea of non-things, a fear of being drowned out // drowned by the non- white men that the liberal groups championed until those groups couldn’t find new populations to rally behind. It feels very stupid and unlikely that such non-issues should cause such tremendous issues (like destroying the foundations of our global economy), but is it surprising? Maybe it would have been predictable to the historians of the the long 19th century that decline would come not from a sudden violent act between nations, but instead after a long period of peace during which the memory of true conflict had faded enough to make not just blaming others for your problems but DOING something about it feel like a desirable course of action.

For a long time in considering China’s rise, I thought the US had nothing real to worry about. I thought that ultimately China’s success would mirror the success of the US, and as in the US a large middle class would emerge that demanded the same rights and protections that we have – namely, the right to free speech. Communist china would become a free market capital democracy in time, like most western nations became even from different cultural starting points. It seemed inconceivable to me that a nation could dramatically curtail free speech with a population of economic parity to ours, without that population either slowly fleeing, or slowly making political demands to unlock it at home. But a lot has changed in 20 years, nothing more than the advent of social media. Free speech means something quite different in the context of a newspaper, or a magazine, than it does on X.com. No technology in our history has done so much to evangelize erroneous, hateful, incorrect, and tribal views as social media, and we don’t seem anywhere close to addressing it as a society. Perhaps our mistake then isn’t in complacency or ennui, it’s in failing to appreciate that social media IS the grave threat to society, a threat we should take far more seriously and be willing to sacrifice far more to combat.

You must be logged in to post a comment.